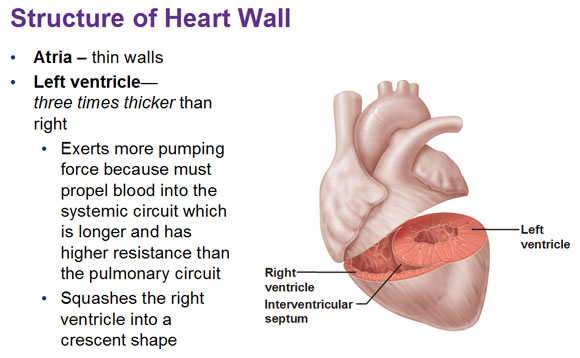

Constantly use the three pictures below to help you orient yourself with the following description of the blood flow.

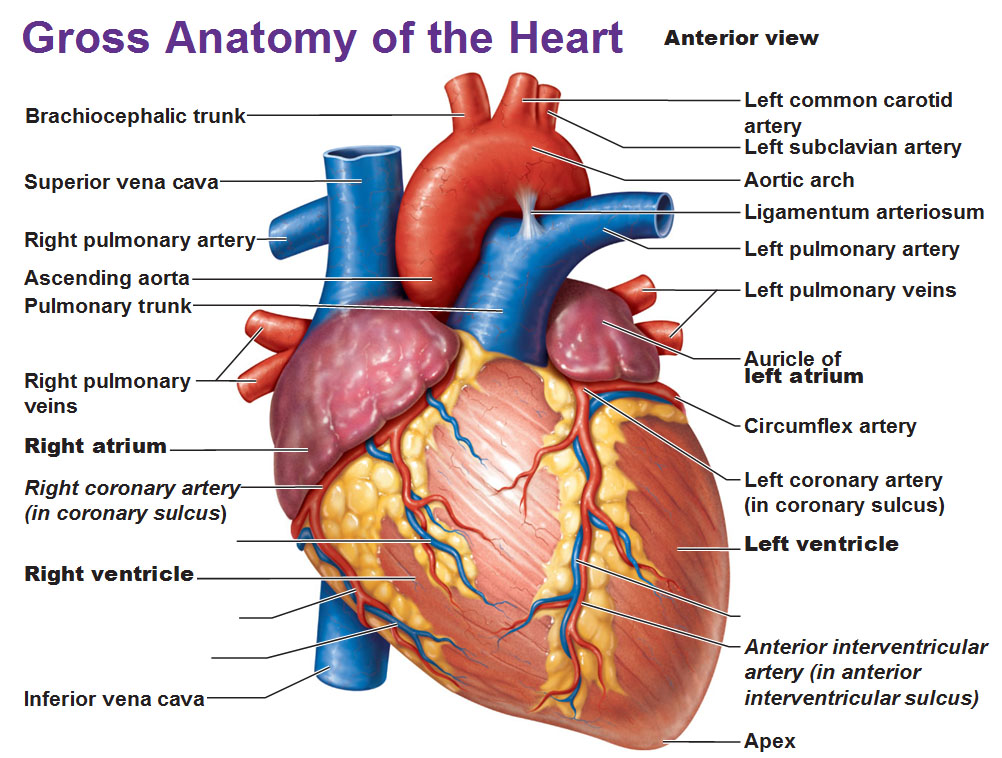

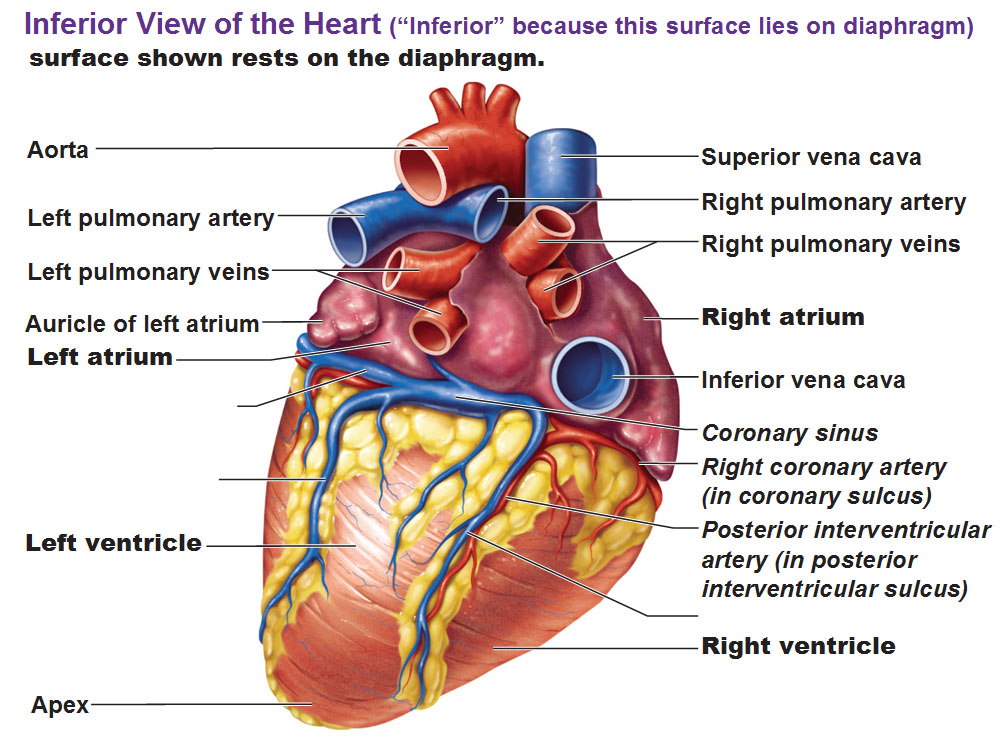

Anterior, Inferior and Cross-Section images of the heart:

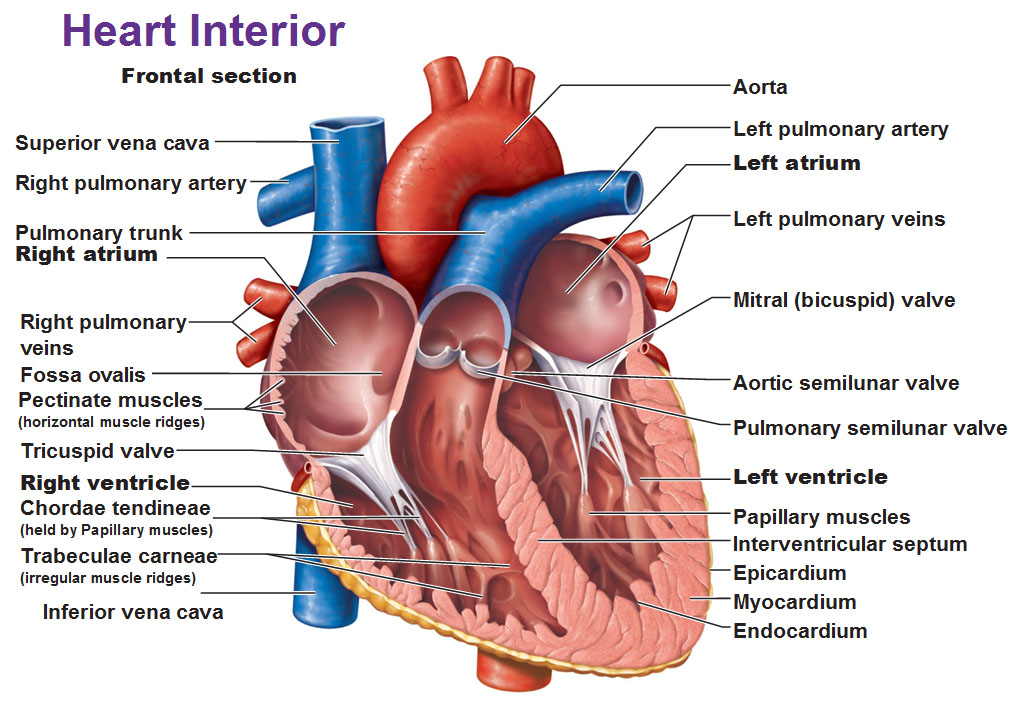

Below: When you slice and take the front off, you could see the atriums and ventricles. If you look inside the right atrium, you could see a big blue blood vessel that opens up into it from the top and another that approaches from the bottom. The right atrium receives blood from both of these inferior and superior vena cava’s (vein=towards the heart, cava=big). The superior vena cava brings in all the blood from the upper half of the body.

Okay so we have blood dumping into the right atrium. The blood falls down with gravity from the right atrium and into this particular passage way, down into this right ventricle. This is bigger than the right atrium and has a thicker muscle wall because the right ventricle does stronger pumping. Lining the hole between them is a valve. This atrioventricular valve is so called because it’s between the atrium and ventricle. The one on the right happens to have 3 cusps to it so it’s called a tricuspid valve (or right atrioventricular valve).

Chordae tendineae are extensions of connective tissue from those valves and we have these tiny muscles that pull on those cords that keep them nice and taut called the papillary muscles. There’s 3 papillary muscles, one for each of the cusps. Then there’s the inner lining called the trebeculae carneae which are muscles but much more irregular that aid in contracting. When this ventricle does contract, it pushes blood up in the only direction it could go out into the pulmonary trunk. It’s a vein and it’s so big it’s just called a trunk. It’s called pulmonary cause it goes to the lungs. This splits into a right and left pulmonary artery. Inside the pulmonary trunk, before that split, blood passes by a valve that’s called a pulmonary semilunar valve (half moon, because someone thought it looks like that). Once the blood goes to the lungs and dumps off the CO2, it goes back in the heart and now it has to go to the rest of the body and we’re going to pump it very, very strongly into the rest of the body.

Freshly oxygenated blood is going to come in from the left atrium, from the left and right pulmonary veins. In humans there are four pulmonary veins, two from each lung. That blood is going to fall with gravity, and the mitral (bicuspid) valve is going to allow blood to dump into the left ventricle. You could see it has the thickest wall of cardiac muscle because the left ventricle has to pump the hardest to pump that bolus of blood into the rest of the body. We’ll also have those same cords (chordae tendineae) anchoring that mitral valve and the same papillary muscles and muscular ridges (trabeculae carneae) lining the inside. When this left ventricle contracts, blood is going to be passed through another semilunar valve, but this time it’s going into the aorta. This is our big major #1 artery. The aortic arch is the arch it forms just before it dips down behind the heart, pumping through the diaphragm (because the heart is sitting on top of the diaphragm) and enters the abdomen where it branches countless times.

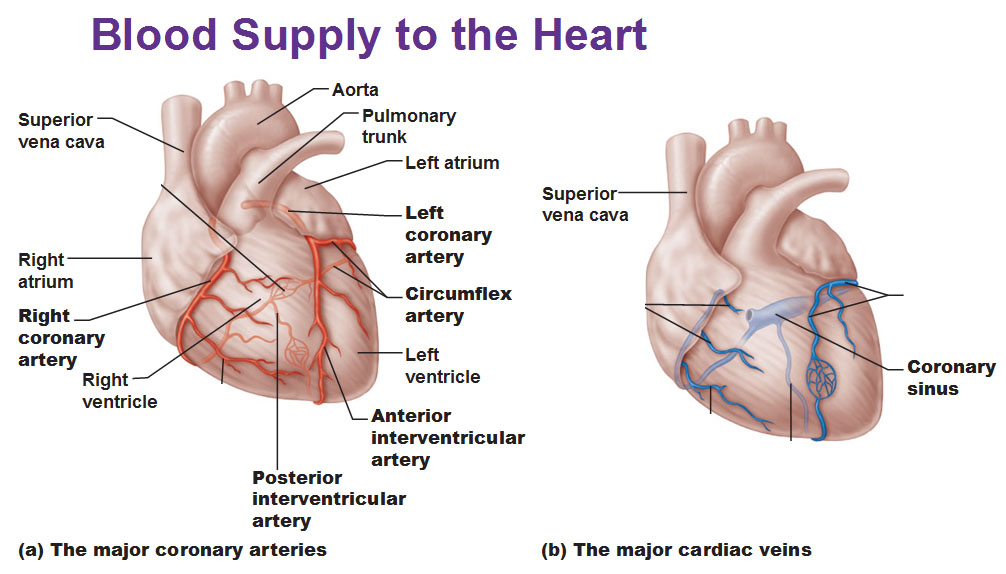

Blood supply to the heart muscle itself

Reference to picture below and previous ones: Of course the heart is muscle and it needs its own oxygen supply. You can’t just keep pumping and not have an oxygen supply of your own. So these red blood vessels that supply the oxygen are called the coronary arteries. You could see them on the surface of the heart. The right coronary artery on the left side sort of defines the division between the atria and ventricles. We’re also going to have a left coronary artery but this is going to split very quickly before it wraps completely between the atrium and ventricle and the continuation of it is called the circumflex artery. The other branch is called the anterior interventricular artery. Of course because the heart does a lot of work it consumes a lot of oxygen and needs carbon dioxide to drain so it has its veins as well that run alongside the same pathways as the arteries. The main drainage you could recognize is the coronary sinus. A lot of the times we’ll see the word sinus come up in these venous systems.

Just to add a little dimension to this, if you cut off the blood supply to the heart, as in if you perhaps cut off one of these AV branches and a blood clot occurred in the coronary artery, so everything distal to that is not going to receive any more blood, then those cells are going to die. That is known as a heart attack, or a myocardial infraction. Another thing that causes that is artherosclerosis or cholesterol. If you build up enough cholesterol and it builds up in the lumen and cuts off oxygen, you get a heart attack.

The sound of the heartbeat

Both atria are going to fill at the same time and contract at the same time to fill both ventricles. Then both ventricles are going to contract together. One cycle of atria+ventricle contraction is considered one “heartbeat.” The sounds we hear come from these four valves shutting. When they close, these cusps actually bang against each other and the cusps hit each other and that’s the sound of the heart beat. It’s the sound of these valves shutting. In a normal healthy heart beat, 70-80 beats per minute is normal at rest. For a very well trained athlete even 60bpm is normal at rest because their heart is stronger, they need to pump less often to do the same work. Diastole is the period of time when blood is filling in the heart chamber. Systole is the contraction.

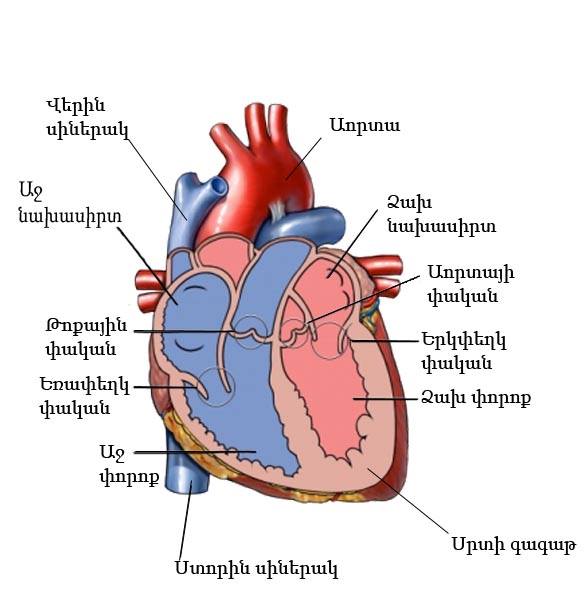

Random Bonus: Heart anatomy in Armenian!

This was kind of a rare thing… and I happen to be Armenian, so I was intrigued and had to throw this into my article.

Use this Table of Contents to go to the next article

YOU ARE HERE AT THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM