I just finished listening to this podcast episode featuring Rafe Kelly on the Move Smart Podcast. This one in particular blew my mind because Rafe Kelley is god damned epic. Almost everything he said throughout was extremely interesting but not everybody has the luxury or discipline to listen to a 90 minute podcast. Everything that was said was so valuable that I feel like it is my duty to help share it with you because the message is so important. Some people are good at interviews. Some people are good at movement. And I’m good at typing. So here goes…

Who is Rafe Kelley?

As the founder of Evolve Move Play, he is one of the best movement teachers in the world. Here’s a video of him playing around. In this very-saturated movement culture, I chose this “Tree Runner” video as it’s quite unique. You think it’s easy to maneuver around trees the way he does? Nope. Nope. NOPE. This man is the real deal…

As you watch this, think… When was the last time you climbed a tree? Do you think it’s easy to do what he’s doing? Let me remind you how scary and challenging it is to climb a tree. I love this video because it becomes more intense and epic as it goes on. If you want something that’s a bit more brachiation-oriented, check this out.

Let’s begin with Rafe sharing the connections between the innate human drive to play and move…

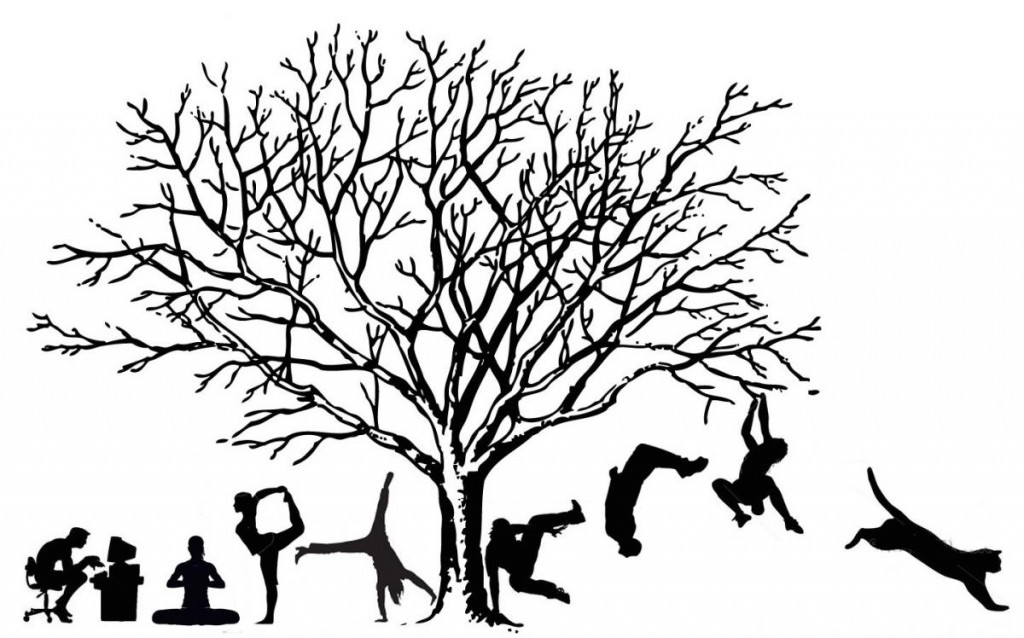

Rafe (~6min in): I was an evolutionary anthropology student and I was reading ethnographies and reading about “child play” all over the world and seeing these same patterns over and over again. Universally, children all over the world climb trees, jump off things, etc. It’s funny that there’s a word for parkour because it’s just universal human play.

For example, aboriginal australians live in these very flat, arid environments. The ethnographer would say that when these kids would see a big rock or tree in the distance, they would get really excited and they would run to the rock or trees and start flipping off of it and jumping off of it and swinging around it. So I was really interested in this idea that parkour wasn’t just a movement practice, but a reflection of this innate play drive. So was martial arts. Every kid wants to roughhouse. Every kid wants to wrestle.

Q: What do we get out of training in an outdoor space that is impossible to replicate even in a very movement-rich environment, like a parkour gym for example?

Rafe (~9min in): It’s almost endless. Essentially the complexity that’s offered by the natural environment and the variety of stressors that you’re adapting to in nature is so much higher.

Take something simple like the floor: In a parkour gym, you’re going to be on a rubber mat that’s almost perfectly flat. So you have a totally static, uniform level of grip on your feet. You have almost no variation so there’s almost no proprioceptive feedback from the ground. The moment you’re outside on dirt and turf and rock, you have to deal with diverse surface grit, how much your foot digs into the surface and the play of your ankle and foot on that surface. So, the kinesthetic feedback that you’re getting from that surface is infinitely higher than the surface at the gym. (Antraniks note: This is why I love walking barefoot.)

And that goes for every object, too: If you want to vault over a tree limb, you have to solve a lot more dimensions of movement than the same vault over a box at a gym. When you’re balancing on top of a tree limb, you have to deal with not only the narrowness of the balance point, but also the tree limb will tip from side to side. It will actually bend and twist slightly. It will bounce as you move on it. It will respond to your force in some unique way. So, proprioceptively it’s just enormously richer and more developmental.

Rafe: Something I noticed early on was that guys who had experience in moving around a lot in nature, adapted very quickly in urban environments. But people who trained in the city had difficulty adapting to the nature.

- I took world class parkour athletes to the trees and saw their jumps shrink by a foot and a half. It’s not only an unfamiliar area but also because the way the light is impacted coming through the branches makes depth perception more difficult. So even something as simple as your vision is changed by having to adapt to that environment.

- Essentially, complexity translates better to simplicity rather than vice-versa. The natural environment is much more complex.

- Thermogenic needs: Can you control the heat of your body whether it’s hot or cold? That’s something an air-controlled gym is not going to teach you. That’s an avenue of adaptation that human beings have and we really need, right? People are constantly miserable because it’s too hot or too cold but they don’t need to be. The same way people don’t need to be weak, they could be strong in their thermogenic capacity. (Related: Physiology behind regulation of body temp)

- Your skin gets abraded by the surfaces a lot more outside than the surfaces of the gym. So when you’re on sand, rock and tree limbs, you’re causing an adaptation of the skin. Skin is the biggest organ and people aren’t training it in anyway. When you start getting on the ground and moving around, that’s loading your skin in a much more diverse way. (Related: Anatomy of your skin)

Q: In addition to all these physical effects, there’s also a psychological impact of being outside, right?

Rafe: Being in nature is good for our psyches. We have this inherent biophilia, this love of living things. Research shows that if you take somebody for a walk through a green space, it’s as rejuvenating to their psyche and their ability to exert will as letting them take a nap. So everybody knows it’s good to be out in nature. It’s good to enjoy this. So, why not compound these benefits of being in a natural space and moving your body? (Antraniks note: that’s why I train at muscle beach! Beach! Sun! Sand! Rings! Grass! Bars! Slacklines!)

Q: I have to drive 30-40 minutes to get to the nearest mountain. How do you manage to access and find parks to move and train in?

- The greatest part of this movement practice is that it doesn’t require a specialized environment. Like, if you’re a rock climber and you want to climb really nice rocks, usually those are not easy to find in the city. But there are trees almost all over every city. So people ask me if I [rock]climb, and sure I do, but I don’t have access to really great bouldering. But I could find bouldering-style trees all over. You just have to develop the vision for it.

- It’s very interesting because people don’t have a vision for play. If you take a kid out in the city park, they’re going to be jumping over and climbing all the things. It’s amazing how atrophied that play drive is in adults.

- People in Australia told me, “You can’t find trees in Australia.” And these are guys who are really interested in natural movement and dedicated trainers. But, I had to take them into the park and point out the type of trees that they could play in. Once they started playing in it and knew what to look for, they started to be able to point out all the trees they could play in.

- You have to recover that mind of a child. And you’ll “see” it. There are opportunities for outdoor movement, everywhere.

(Antraniks note: There’s also workoutmaps.com and this map and this resource to help you find official parks and playgrounds as well.)

“You have to redevelop this awareness, vision and intuition around nature and your immediate environment so that you could tap into the entire playground that is the natural world we live in.”

It’s a form of movement intelligence. It’s a form of visual acuity. Not only are we not adapting in our training and in our lives to be stronger with our muscles and our skin, but we’re also not adapting visually. We don’t have the ability to use our peripheral vision or to pick up patterns very well. Something like gathering: People who gather mushrooms have this intense visual intelligence to be able to scan this environment and pick up. So it’s the same thing, when you go play in nature, overtime you see more and more opportunities but you have to expose yourself to it first.

“Parkour and gymnastics are almost inversions of each other”

- Parkour in the traditional sense (not the freerunning aspects of it) was was essentially a set of very simple movements: Run, jump, vault, and climb. And what you did with those movements were to seek environments that offered challenge and diversity and then express those same movements in more challenging environments.

- Whereas in gymnastics it was the opposite: You had a very simple set of environments (the apparatus) and you’re constantly working to express greater movement amplitude and complexity in that [relatively simple] environment. And of course everybody does both and one is not right or wrong, but we need both… And I started to think of this as…

Internal freedom vs External freedom

Rafe (23min in): When Ido Portal talks about Self Dominance, I think of that as Internal Freedom meaning, Can you express any sort of movement pattern that you want just with your body in relatively simple space? And then can you take your movement capacities and make them more applicable in a broader range of situations? And that’s what I think is External freedom.

At my seminars, we begin with the internal and look for relatively simple environments like a grassy field and work on movement flow so people can start experiencing the sensation of flow. Then we move them into nature and they start expressing themselves within more complex environments.

Having the ability to flow around on a flat floor (internal freedom) is amazing, but does that make you a great mover? Or is that only part of the equation?

- Rafe: I would say it’s a very limited part of the equation. They’re both great and as you become a high level mover, you should definitely explore internal freedom for sure. The greater internal freedom will give you more potential for external freedom. But I think in terms of the current Movement Culture and Parkour, there’s too much focus on the internal-side. There are people I know that could do OAHS, a bunch of ring skills, a Press HS, a OAC… but they can’t jump… They can’t run well from one place to another… they have no ability to put together sequences… they don’t have a vision for movement outside and I think it’s a very limited place to be because you’re still in a box.

- I think when you have a movement practice that allows you to express yourself outside, to be the man who runs and whom nothing stops. Personally, I feel that’s more powerful. I think, feeling like you’re able to deal with a fight, feeling like you can dance and express yourself. I think that’s a type of freedom that is more interesting to me in many ways and if we had to think about what humans had to be good at to survive as a species, one arm handstands are not a part of that equation.

- For example, I found handstands to be an esoteric, abstract pursuit to true movement capacity. (Video Source)

I’ve met people who could do multiple OACs but are really poor at climbing! Are there any other places where you see this disconnect happening where there’s a high level of strength but the movement skill isn’t there?

- Rafe (27min in): I think our movement and fitness in general is really driven by looking for these isolated aspects of movement, fetishising them, and then missing the forest from the trees. The movement culture is an outgrowth from the fitness world and the fitness world for a long time has been about looking at how someone who moves well, ends up looking.

- They’re trying to replicate the physical appearance without replicating where it comes from. So having abs, biceps and pecs (or a tight butt if you’re a girl), doesn’t mean anything about how you could move. And the way people train for that is by taking really simple variables out of movement.

I wanted to talk about this concept of “Movement aliveness.”

- Matt Thornton started looking at Martial Arts and started to see which one gave people effective skills and which one didn’t. He found that the difference is in what he called “aliveness.” In martial arts context, he defined aliveness as the ability to deal with energy, timing and rhythm. You could have a really powerful [solo] motor program, but if you’re never used to dealing with another persons energy, you can’t apply it.

- It’s like, if you want to do a handstand really well, you have to train your wrist for extension and get the proper wrist extension. Will you be able to do a handstand after that? Nope, because that’s only one variable.

- When you go into alive movement, there’s an aspect of seeing all the variables and trying to solve them. But it also makes us FEEL more alive inside. Most parkour guys spend time doing isolated techniques in perfect environments.

Comfort vs Freedom!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Rafe (41min in): When we push ourselves to the limit, we know ourselves on a deeper level. We have a culture now that has provided, better than ever any culture before in history, this potential for comfort. So people think “Okay, I don’t like to feel cold”, so they avoid that experience and keep the heat up high. Then they realize their ability to buffer that cold has decreased. So now what used to be a tolerable temperature, becomes a colder temperature. They have narrowed the window of what they could deal with comfortably. So now, the world is actually MORE stressful for them.

When we seek comfort, we don’t find happiness. We actually, progressively, take away our resilience from the world and take away our ability to maintain our happiness. When we seek some level of struggle, something that forces us to our edge of adaptation, then we grow in a way that allows us to better sustain our happiness.

In mountaineering, there is a quote: “It’s not what the man does to the mountain, it’s what the mountain does to the man.”

And that’s true with every movement practice. What we get out of it isn’t that we accomplish a cool trick. It’s what that process opened up within ourselves and how that freedom we have now in our world, supports our own sense of well being. And there’s costs, too, because you don’t want to push yourself to the point of pain! 🙂 Slowly seek these experiences progressively. Seek the experiences of the edge of what we’re capable of. This is a profound way of becoming a more embodied human being.

Play in the form of roughhousing, wrestling, etc…

At my seminar, the first time a woman gets to rough-house and slap a person, they have this huge smile on their face and a giggle that comes out because it’s something they’ve been told they can’t do their whole life. Something that we’re profoundly afraid of in our culture is this aspect of our physicality and what it can do. So, to be given permission to do that, in a safe place to express that physicality is freeing in a profound way. There’s a psychological aspect to it because it’s something we all actually want to do on some level, and then are told NOT to do. And so when we take that away, it’s really freeing for people. And we want to do it because being able to fight and defend yourself is a foundation for being an effective human history throughout human history.

If you look at archeological records: In peaceful cultures about 10%, and in war-like cultures, something about 60% of males would die by violence, hunting accidents or warfare. This was a profoundly shaping part of the human experience. It’s great we don’t have to worry about all our friends being killed or abducted anymore, but we have to realize that those are our forefathers and people who won those conflicts are people whose genes that we carry. So this capacity for violence is actually something that’s very deep in us and we can’t deny it. You have to find positive ways to express it!

Closing thoughts

Honestly, the rest of this podcast is equally profound. But I have typed out enough. And I am going to go out and go play now because I am so inspired. If you want any cool resources, check out my comprehensive handstand tutorial and keep an eye out for my rings-oriented bodyweight training routine that’s coming out this month!